Having taught Physics, I am aware that the use of textbooks in STEM lessons is the exception rather than the rule. Even before the advent of digital technology in the classroom, Lunzer and Gardner (1979) observed that less than 10% of an average STEM lesson was spent reading. Of this time, over 90% was in bursts of less than 10 seconds, primarily reading from the board, worksheets or posters and NOT from textbooks. Wellington and Osborne (2001) note a similar trend. In 2011, I decided to test this myself, and observed less than 9% of lesson time was spent in reading, with a average of 1 minute 9 seconds reading the textbook per 40 minute Sixth Form lesson, of the lessons in which the textbook was actually used at all. Now, this is clearly not generalisable even to other STEM lessons, let alone to other subjects. But I do seriously question the financial sense of buying textbooks that are virtually unused. I would love to be challenged on this point – I would love to find out that every other STEM teacher in the country integrates literacy more into their lessons. My whole doctoral research is predicated on the conviction that literacy and language is crucial to learning science. However, I do question that traditional textbooks are the way to promote literacy.

Textbooks are cheaper on a singular basis, are not subject to the whims of wifi access and battery and are more likely to survive a few splashes of hydrochloric acid and other classroom hazards. Certainly, textbooks have a longevity, a permanence, a physical presence. There are many contexts in which a paper-based textbook is more appropriate and supports learning more than an electronic resource, as electronic resources currently exist. However, the very permanence of textbooks renders them prone to rapid outdating (especially when the curriculum seems to change every time you turn around) and inflexibility. You can do many more things, learn many more things, with a tablet than you can with a textbook. Educational resource availability is increasing exponentially online, with a quaquaversal array of communities and individuals creating and communicating good practice, resources and insights.

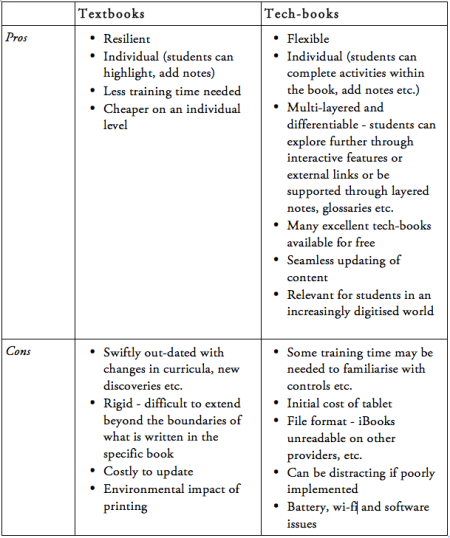

However, educational research into edtech has an unfortunate lag time in many cases – several recent journal articles I have read define ebooks as any digital text, including pdf versions of paper textbooks (even scanned versions). So, I am distinguishing here the concept of tech-books, which use a digital pedagogy to promote and enhance learning through the educationally relevant integration of electronic resources. Rather than solely textual delivery, tech-books include audio, video and interactive elements, where and as appropriate, to support learning. Currently, there is little research that directly indicates gains in reading comprehension or content learning through ebooks. However, given that this research suffers from an outdated definition of ‘ebook’, it is unsurprising that no difference in reading comprehension between textbooks and ebooks has yet been formally reported. That does not mean that tech-books, with enriched content chosen for learning and not for novelty, do not offer gains unavailable through textbooks, as outlined in the table above. All it means is that we need to keep testing, keep trying, keep learning about the tech and about our teaching.

Edtech is not about pushing digital resources, or about jumping onto a bandwagon dictated by management. It is about trying to improve the learning experiences of teacher and student. But if we don’t learn, we can’t teach. Experiment, explore and evaluate the available tech-books and textbooks and make a decision based on the needs of your students for a specific lesson and context, rather than deciding that every lesson must (or must not) be digitally based. That said, to effectively teach is to effectively learn and that is why I try to constantly learn about new pedagogies, new tools, new contexts for learning; to be a digital experimentalist and explorer rather than a digital evangelist.

The centre of education must always be learning, and that is always what we try to promote, in the most effective ways available to us – textbooks, tech-books, whatever works for your learners, in your classroom, with your level of confidence and training. If there can be only one winner, it must be student learning.

References:

Lunzer, E., & Gardner, K. (1979). The effective use of reading.

Wellington, J., & Osborne, J. (2001). Language and literacy in science education. McGraw-Hill International.